Locator: 48490LDCS.

RBN Energy: tech giants increasingly turning to natural gas to power data centers.

The pace of announcements for planned data centers accelerated in 2024 and has continued to gather steam in 2025, with natural gas-fired power plants emerging as a frequent choice, along with nuclear power, to provide the around-the-clock electricity that large-scale data centers want and need. In today’s RBN blog, the first in a series, we’ll detail plans by several well-known energy firms to construct new gas-fired plants that would produce electricity specifically for data centers.

Let’s start with some data-center basics. As we discussed in Storm Front, a data center (see photo below) is the home for hundreds or even thousands of networked computers that process, store and share data. Data centers — many of them owned and operated by tech giants — are among the most energy-intensive building types, consuming up to 50 times the energy per square foot of a typical commercial office building, with electrical demand at larger facilities ranging from 100 megawatts (MW) to 2,000 MW. (For perspective, as we noted in Just Can’t Get Enough, a city the size of Lubbock, TX, — population 267,000 — only requires about 700 MW.) Demand for data centers has grown exponentially with the expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT and Perplexity, which require far more computational power — and energy — than conventional Google searches.

The Interior of an Amazon Data Center. Source: Amazon

Why Natural Gas?

As we noted in Dive In, the main reason firms are considering natural gas to power their data centers is that it is a consistent source of round-the-clock power and can be deployed at scale, usually within a reasonable period of time. Recent headlines for power deals indicate that tech firms are willing to pay up for power — as long as it is reliable — so while gas generation is relatively cheap, that’s more of an added benefit rather than the key feature.

Importantly, gas-fired generation generally can be deployed relatively quickly, allowing for solutions that are quick and nimble. A case in point is a data center in Memphis, TN, where 14 mobile gas-fired generators were brought in to help power a 150-MW facility being developed by Elon Musk’s xAI. (We’ll discuss this development and mobile generators in more detail in Part 2.) In contrast, while the buzz around nuclear is surging due to its reliability and the fact that it doesn’t produce GHGs, it is more expensive to build and has higher hurdles to clear than gas, with years of permitting headaches and construction in the best of circumstances (see We’ll Be Together).

One big catch with gas-fired power is that it generates GHGs and many big-tech companies have set ambitious goals for reducing emissions. But as you’ll see below, some firms are addressing this by incorporating carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) into their data center plans. (Note: Developing CCS projects comes with its own set of challenges — see California Sunset, Stuck in the Middle With You and The Longest Time for more.)

Gas Demand for Data Center Power

So, what does the surge in data centers mean for natural gas demand? Let’s start with a facility requiring 1,000 MW, or 24,000 MWh over 24 hours. Although estimates vary, by our calculations, a combined-cycle plant would need about 6.5 MMcf of natural gas per hour, or around 157 MMcf/d, to generate that much power. The calculation can vary based on several factors, but in short, we consider the information we know. (*Our calculation is at the end of the blog, if you’re interested.)

It’s worth noting again that these numbers vary based on numerous factors, including the age of the gas plant and its heat rate and cooling factors. Data centers require significant cooling, which can also use up more energy. (There’s also the need to get natural gas to the site, which could require a new pipeline or a lateral from an existing pipeline.) And that’s just for one data center. An S&P Global report in October 2024 predicted that by 2030, data center demand for power will increase U.S. gas needs between 3 Bcf/d and 6 Bcf/d — even with wind, solar and other power sources meeting sizable portions of data center power demand. To put that figure in context, dry natural gas production in the Lower 48 has been averaging about 106 Bcf/d in recent weeks, with net imports from Canada at 5 Bcf/d, putting total supplies at around 111 Bcf/d. For comparison, feedgas demand for the U.S. LNG export facilities already in operation is around 15 Bcf/d. (For more, see our daily NATGAS Billboard report.)

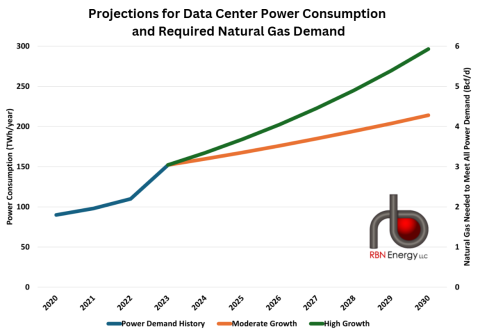

The rate of growth for data center power demand is hard to predict, but we can get a good indication from a 2024 Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) report we addressed in Smarter Than You. The report represents four projections for data center demand. Figure 1 below highlights two of these scenarios, excluding the lower and higher extreme cases. These forecasts are based on historical trends, estimates of internet traffic, storage demand, and expectations for computational intensity and the prevalence of AI models. The blue line represents the average historical electricity consumption of data centers over the 2020-23 period.

Figure 1. EPRI Projections of Data Center Power Consumption. Sources: EPRI, RBN

In the Moderate growth scenario (orange line) with a 5% compound annual growth rate (CAGR), data center electricity demand is expected to reach a midrange value of 214 TWh/year (terawatt-hours) in 2030. If all that additional load were to be served by gas generation, it would be roughly equivalent to 4.2 Bcf/d (right axis in Figure 1). For the High growth scenario (green line) with a 10% CAGR, the midrange 2030 demand is projected to be about 296 TWh/year (5.9 Bcf/d) — essentially double the 2023 figure of 150 TWh/year (3 Bcf/d). Forecasts vary widely for what the net impact on natural gas demand will be when considering other initiatives to increase efficiency or phase out gas usage in certain applications. But, in just about any scenario, for data centers and other electrification initiatives, we’ll be requiring a substantial power-grid expansion.

We should also note that forecasts for data center power demand — already a moving target — were complicated in January by the introduction of DeepSeek’s R1 Model, which takes a different approach and is reportedly able to perform complicated tasks with less reliance on high-tech chips — and ultimately require less power. That’s an indication that power demand growth for data centers might not be as robust as originally predicted. We expect the technical advances will continue and the industry will be eager to figure out how to complete more AI tasks with fewer resources. On the other hand, increased efficiency could actually lead to more demand for power as it reduces the cost — a concept known as Jevon’s Paradox. So, it’s possible that more energy-efficient models could lead to greater use of AI and increased data center power demand.

For now, we’ll focus on a few of the major energy firms that intend to provide gas directly to data centers for power generation. As you’ll see below, some of the companies haven’t revealed partners yet, and we should also note that project announcements are coming quickly, so not every significant announcement is listed here. (We’ll dive into the deals that directly involve giant tech firms like Amazon, Google and Meta in Part 2 of this series.)

Diamondback Energy

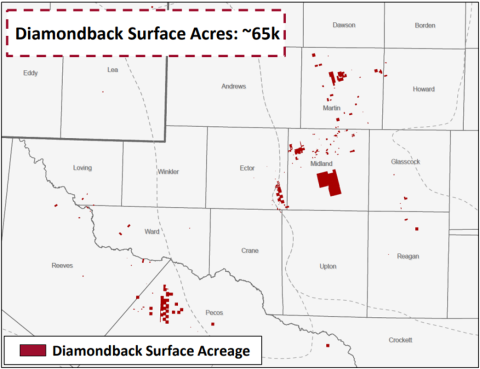

Diamondback Energy, a giant in the Permian Basin, is in talks to form a power joint venture to sell electricity to AI data centers in West Texas, the company announced in its fourth-quarter earnings call on February 25. There are few details on this plan, but Diamondback, the largest independent oil producer in the Permian Basin, said it intends to look for an equity stake in a behind-the-meter, gas-fired powered plant that would be built on some of its 65,000 acres (red-shaded areas in Figure 2 below) in West Texas.

Figure 2. Diamondback Energy’s Surface Acreage in West Texas. Source: Diamondback

A co-located power plant is one placed at or near a data center, allowing the facility to have direct, behind-the-meter connections to the power being generated. That means the power won’t flow through the existing transmission grid. The shale producer could benefit by supplying some of its natural gas to the plant and receiving some of that power for its own operations, executives said on the conference call. Diamondback could also provide water for data center cooling. This could be an ideal solution for producers who are seeking to get stable pricing/offtake for their natural gas. As we’ve blogged about many times, power transmission lines can be every bit as difficult to permit and build as pipelines (see Don’t Pass Me By). And while new gas pipelines are being added at a rapid clip, spot deals at Waha frequently go to negative pricing when marginal gas production gets stranded in the Permian Basin (see Prognostication #2).

Much more at the link.