A halving in the oil price since June has upended assumptions by developers that cheap U.S. LNG would muscle into high-value Asian energy markets, which relied on oil prices staying high to make the U.S. supply affordable.

The floating 8 million tonne per annum (mtpa) export plant moored at Lavaca Bay, Texas advanced by Houston-based Excelerate has been put on hold.

The project was initially due to begin exports in 2018.

Excelerate's move bodes ill for thirteen other U.S. LNG projects, which have also not signed up enough international buyers, to reach a final investment decision (FID). Only Cheniere's Sabine Pass and Sempra's Cameron LNG projects have hit that milestone.

*************************************************

Spouse of the Rising Sun—No LNG Divorce Imminent, Despite It All Monday, 12/29/2014

Published by: Housley Carr

It would be an understatement to say that the worldwide market for liquefied natural gas (LNG) is in flux. LNG production is up and heading higher, oil—and LNG--prices are down sharply from a few months ago, and Japan and other big consumers of LNG are more interested than ever in mitigating price and supply risk. All this comes as Japan, a primary target of prospective U.S. and Canadian LNG export projects, is grappling with the need to restart dozens of idled nuclear units so it can reduce the oil and LNG imports that have hurt its trade balance since the Fukushima disaster nearly four years ago. Today we consider recent developments and how they may affect Japan and its potential LNG suppliers on the North America side of the Pacific.

Despite recent setbacks, Japan remains an undisputed economic powerhouse, the third-largest economy in the world behind the U.S. and China. But the island nation depends more than ever on imported oil and natural gas (in the form of LNG) to run its power plants and factories and to heat its businesses and homes. As we said in the First Episode of our “Spouse of the Rising Sun” series, Japan was already the world’s leading LNG importer (accounting for about one-third of all LNG imports) in March 2011, when a 9.0 earthquake triggered a tidal wave that devastated Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s six-unit Fukushima Daiichi nuclear station northeast of Tokyo. Within two months of the disaster, most of Japan’s other 48 nuclear units were offline, and by September 2013 all of them were. Given that nuclear power had been providing 30% of Japan’s electricity prior to Fukushima (with fossil-fired units providing almost all the rest), the industry-wide nuclear shutdowns forced wrenching change. Oil and LNG imports rose to fill the nuclear gap and, as we said in Episode Two, the pace of nuclear-unit restarts is likely to be slow and the heightened need for oil and LNG is likely to continue. What’s changed over the past few months though, is that a lull in LNG demand (in Japan and elsewhere in Asia) has created a supply surplus and a buyer’s market. Also, as we know all too well, the price of oil has fallen precipitously and shows no sign of a quick rebound. These changes (and rising LNG production in Papua New Guinea, Australia and—soon—in the U.S.) have given Japan the hope of reining in its fuel-import costs in general, and its LNG costs in particular.

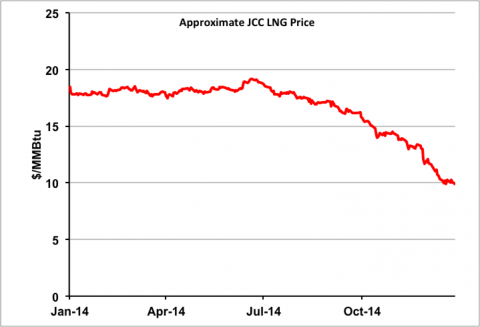

The very liquid worldwide market for oil enables Japan and other Asian oil importers to take advantage of currently low oil prices. In addition, because the vast majority of Asian LNG contracts index LNG prices to a basket of imported oil known as the Japanese Crude Cocktail (JCC - see “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue”), LNG-importing countries also are benefiting from much lower prices in recent months. Figure #1 shows an approximation of the JCC based on Brent prices since the start of 2014, falling from close to $20/MMBtu in July to $10/MMBtu in December. Add to that the facts that demand for LNG in Japan and South Korea this past summer and fall has been flat, and that new LNG production expected online soon will add to market supply (fully one-third of the output of Chevron’s mammoth Gorgon LNG project in Australia—set to start exporting in mid-2015—is not under long-term contract so will hit the open market) and you have yourself an LNG price-sag of major proportions. In December 2014, spot LNG prices in Asia (a better leading indicator than the JCC contract price) are below $10/MMBTU and they could fall even more by the spring of 2015 if it’s a mild winter and LNG stockpiles continue to build.

Figure #1

Source: RBN Energy (Click to Enlarge)

That’s great news for LNG importers, of course, but it’s a real headache for companies trying to develop new LNG export facilities—and for U.S. and Canadian natural gas producers hoping to lock in long-term deals to sell gas for export as LNG. Consider a 20-year LNG contract that a Portuguese utility, Energias de Portugal (EdP), reached in December 2014 with Cheniere Energy’s planned Corpus Christi LNG export facility. Under the deal, EdP will take up to 0.77 million metric tons per annum (MTPA) of LNG (the equivalent of 108 MMcf/d of natural gas) and pay Cheniere a liquefaction and LNG loading fee of $3.50/MMBtu plus 115% of the final settlement price for the Henry Hub natural gas futures contract for the month in which the LNG shipment is scheduled. If a Japanese buyer made an identical deal, and if the Henry Hub gas price were, say, $4/MMBTU, the cost of gas delivered to Tokyo would be $4 (for the gas) plus $3.50 (for the base liquefaction fee) plus 60 cents (15% of $4, the supplemental liquefaction fee) plus $2 for shipping (roughly) and plus $1 (again, roughly) for regasification in Japan. That comes to about $11/MMBTU--a buck or more above the current LNG price in Asia. Then (for the Japanese LNG buyer) there’s the risk that U.S. natural gas prices could rise, putting U.S.-sourced LNG further out of the money in a low-price LNG market. It’s all more complicated than this, of course. For one thing, despite efforts by Japan, Singapore, China and others to establish a liquid trading market for LNG, that goal has proved elusive. For another, as part of Japan’s effort to mitigate LNG price and supply risk, its utilities and other buyers have been actively seeking U.S. (and Canadian) sources of LNG. Still, the current slumps in oil and LNG prices (and in Asian LNG demand) are generally not good news for companies trying to develop U.S. and Canadian LNG export facilities.

That doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that Japan (and South Korea, China and India) won’t commit to buying additional LNG from the U.S. and Canada in the future. As we said, LNG buyers (Japan being a prime example) want supply diversification, and adding a few gas-price-indexed LNG contracts into their mix wouldn’t be a bad thing from a risk-mitigation perspective. Also, it’s reasonable to predict that oil prices will be higher four to six years from now than they are today, and that’s the period in which most new Asia-focused LNG export projects in the U.S. and Western Canadian projects (like Veresen’s Jordan Cove project in Oregon; see “New Kid in Town” and below) would come online.

Jordan Cove LNG

Source: Veresen (Click to Enlarge)

Then there’s the issue of Asian LNG demand—and, given the focus of this blog, Japanese demand in particular. Sure there’s been some recent softness in Japan’s demand for LNG (mostly tied to mild weather), but LNG imports in the Land of the Rising Sun remain well above their pre-Fukushima level (about 89 MTPA now, versus 71 MTPA in 2010), and its likely they will decline only slightly–or even stay flat--as most of Japan’s nuclear units are restarted over the next few years. (You may be wondering if, with oil prices so low, Japan will ramp down its use of gas-fired generation and ramp up its use of oil-fired generation. The answer is, “Not to any significant degree.” Japan has been trying to reduce its oil dependence for years, mostly with emission-reduction and climate-change goals in mind. And all of the new, highly efficient generating capacity being developed in Japan is fired by gas, not oil.) The bottom line is that while all this is clearly a challenging time for those interested in selling LNG at a solid profit to the Japanese, Japan is not in any way inclined to end its long-time marriage to LNG. As we said, LNG imports in the current Japanese fiscal year (FY2014, which ends March 31, 2015) are expected to total 89 MTPA (according to a December 2014 estimate by Japan’s Institute of Energy Economics), and even with the oil price decline and LNG demand slump factored in, LNG imports are only seen slipping to 85 MTPA in FY2015, which runs through March 2016. So, as Japan’s older, oil-indexed LNG contracts roll off and Japan seeks more supply diversification, there is probably room for a few more LNG-supply deals with the U.S. and Canada. Patience may be required though; the oil price collapse has everyone taking a deep breath and a second—and third—look at everything we previously assumed to be true in this market.